There was hardly time to panic.

One woman, flung from a window, landed on the ground outside, her face all but buried in the dirt. Two others, sitting in the back, were hurled airborne the length of the bus and slammed into the driver’s seat.

Three people died and even the lucky ones — the wounded who survived — suffered horrific injuries: concussions, compound fractures, brain trauma, broken ribs.

A tour bus, owned by the New York company AM USA Express, had overturned on a highway off-ramp in Delaware, coming to a rest at the base of an embankment. Bodies were strewn about the bus’s twisted shell. But the damage done that day, Sept. 21, 2014, was only the beginning. As the case passed from the hands of medical professionals to the legal system, the victims and their families were thrust into a fresh set of ordeals.

Insurers for the bus company (and later the travel agency that arranged the trip) said they anticipated that the claims stemming from the crash would exceed the money available under the companies’ insurance policies. So they asked a federal judge to divide the money into settlements. More or less pitted against one another, the victims and their relatives were forced to come to court to tell their stories, reliving an experience that many were still recovering from.

As brutal as the crash was to those involved, it was not unheard-of. Last month in Queens, there was another bus crash that also killed three people. Although the investigation into the Queens crash has only just begun, the aftermath of the 2014 crash could provide a guide to its survivors. As told through interviews, legal filings, courtroom testimony and police reports, the story of the Delaware crash indicates that the financial and emotional effects of tragedies like these ripple on for years, and far outlast the initial physical impact.

“Even today,” Gary R. Brown, the magistrate judge who oversaw the settlement of that crash, wrote in June, the victims were still grappling with “getting on with the difficult process of healing.”

The 50 passengers were from all over: India, Romania, Turkey, Ecuador, Australia as well as New York, New Jersey and California. They included students and sisters-in-law, single friends and married couples. Among them were newlyweds from Algeria.

The three-day excursion, arranged by E-World Travel & Tours, began in Manhattan with a stop planned in Niagara Falls. The tour was meant to head on to Washington and then to Philadelphia, but the bus broke down in upstate New York, forcing the passengers to wait for hours at a shopping mall until a replacement, a 1996 Setra, showed up.

The whirlwind nature of the trip was magnified by the tight schedule set by E-World and the breakneck pace kept by the Setra’s driver, Jinli Zhao, whose erratic driving had unnerved many passengers.

Mr. Zhao seemed irritated, angry, even rude, often rushing the passengers at rest stops, some of them later reported. At least once when a passenger returned late to the bus, Mr. Zhao began to drive away, as though he meant to leave them, one passenger told the police.

Mr. Zhao also seemed distracted behind the wheel. He would eat while driving, passengers recalled. He argued frequently with the tour guide and constantly downed energy drinks. And he was frequently on his cellphone, they said.

He veered near cars in adjacent lanes, accelerated dangerously and then stepped on the brakes, passengers said, cutting off other vehicles. He shifted lanes at such high speed that one passenger said he felt the bus swaying back and forth.

The tour guide, Allan Ge, told the passengers that Mr. Zhao had not slept in a while, Melis Seker, a Turkish college student who was then 19, later told the police. Mr. Ge told the group that “if the police ever stopped the bus and found that the driver had not had enough sleep, then they would be forced to stay and rest,” Ms. Seker said.

The crash occurred on a stretch of roadway in Delaware that investigators said the driver was unfamiliar with. Confronted with traffic on Interstate 95, he and Mr. Ge decided to take a different route. Mr. Zhao consulted his GPS and turned onto a long, curving off-ramp leading from State Route 1 toward U.S. Route 13.

As they pulled onto the ramp, several people stood up and shouted for the driver to slow down, one passenger told the police. When the bus began to tip, luggage tumbled from the overhead racks. People started screaming.

An Algerian man, Karim Fellahi, who was with his wife, Ihssene Kerchouche, on their honeymoon, remembered seeing the driver lose control.

“I just had the time to say to Ihssene, ‘Be ready for the impact,’” Mr. Fellahi, 36, testified, “because we were sure that we are going to die. We closed our eyes and we waited to die.”

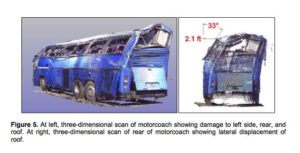

The bus was off the road now, careening into a sloping area of bushes. It went upside-down, turned on its roof and skidded partway down a grassy embankment, rolling again and landing with a shudder on the driver’s side.

Moments later, Mr. Fellahi said, he opened his eyes to a barely identifiable structure. “I couldn’t recognize the roof,” he said. Ms. Kerchouche, 29, had disappeared; even her seat was gone.

“I heard her screaming my name,” Mr. Fellahi said. “It was like she was far, very far, from me.”

He found his wife outside the bus, facedown in the dirt and covered by other passengers. Her mangled right forearm was dangling, connected to the rest of her arm by a piece of skin.

Another passenger testified that she and her sister were propelled through the air at the moment of the crash, flying forward and slamming into people and broken bus parts.

She could not move her arms or legs and felt an unbearable pain in her pelvis, which had been fractured by a large piece of metal.

The Delaware State Police arrived to a scene of carnage: a twisted metal shell and dozens of bodies strewn around it. A 400-foot-long trail of tire marks streaked across the road.

As passengers struggled to escape, Eyup Bahsi, a 30-year-old Turkish man, looked in vain for his wife, Idil. Also 30, she had been sitting in the window seat beside him. Mr. Bahsi finally found her, conscious and seated with her legs pinned underneath the bus. She was trying to pull herself free.

Ms. Bahsi was also having trouble breathing, Mr. Bahsi said, and he gently helped her lie on her back. He tried to clear her mouth of dirt.

She squeezed his hand, opened and closed her eyes and tried to speak, but Mr. Bahsi said that he could not make out the words. He sought to reassure his wife, telling her to just stay calm, that an ambulance was on its way. Ms. Bahsi eventually reached a hospital, where she underwent several operations. She died later that night.

The National Transportation Safety Board concluded that the probable cause of the crash was excessive speed. Mr. Zhao, the driver, claimed that he was feeling ill before the crash and had “blacked out.” But the safety board said that the evidence suggested he was not incapacitated.

The board eventually determined that Mr. Zhao had driven a total of 14¾ hours that Saturday, exceeding the 10-hour federal limit. He also did not have the requisite 8 hours off before he set out on the road again.

The board found that the driver’s cellphone records showed he was routinely making and receiving calls and was using his voice mail when the bus was moving, although not when it crashed.

Mr. Zhao, 56, later pleaded guilty to three counts of operating a vehicle causing death and received probation, Delaware court records show.

This month, when a reporter visited his apartment in Queens, Mr. Zhao loomed silently in the background as a young man, who did not give his name but said he was Mr. Zhao’s son, stood in the doorway. He said his father was so “scarred” by the crash that he hardly spoke of it, even to his family.

“What’s past is past,” the son added.

During the litigation, Mr. Zhao was deposed by victims’ lawyers. He testified that when he arrived from New York to fetch the tour group in the Setra, he informed the guide, Mr. Ge, that he was already “very tired.” Mr. Zhao said he had explained to Mr. Ge that if they kept to their plan, his hours would be “a lot over the limit.” He said that Mr. Ge responded there was “nothing he could do.”

In an interview, Mr. Ge said that he did not recall Mr. Zhao looking “really tired.” An E-World supervisor, David Lo, described the travel agency as “an innocent victim” in the crash. “We cannot control the driver,” Mr. Lo said. “We cannot control the bus company.”

The bus was insured for $5 million — the minimum required by law. The insurers filed court papers saying they anticipated that the claims from the crash would exceed their policies, and they ultimately deposited the full $5 million with the court and left Judge Brown to allocate it.

Lawyers for the victims said that this approach, while hardly ideal, was nonetheless their best chance to compensate their clients. The lawyers had learned that AM USA Express had sold its remaining three buses and gone out of business; E-World, they said, also had few assets.

The process was designed to avoid a lengthy court fight, but because the pool of money was limited, it meant that if some passengers got more, others would get less. “On a certain level, it’s a zero-sum game,” said Brian M. Levy, a lawyer for 21 of the claimants.

In order to understand the impact of the crash, Judge Brown held two days of investigative hearings in April. What had previously been a dry legal matter suddenly became excruciatingly human.

Around 10:30 a.m. on April 26, several of the victims — some having traveled from continents away — filed into the courtroom in Central Islip, N.Y. Judge Brown had set out boxes of tissues, and as the day went on, he stopped the proceedings several times to apologize.

“I understand this was a horrific event,” he said, “and we’re going to do everything we can to get you through this as painlessly as possible.”

The first witness was Shilpa Lagishetty, who told the judge that she had suffered a traumatic injury to her right eye socket. Even after surgery, Ms. Lagishetty said, she had constant headaches and could no longer see things that were more than two feet away.

There had also been an emotional toll. “I still have sleepless nights,” she said. On the morning of the crash, she recounted, a woman had asked her to swap seats; she did. The woman died in the crash, she said, beginning to cry.

“I’m so depressed,” she added. “That lady had a son. I can’t imagine me in that position.”

Addressing the judge next was Mr. Bahsi, who had flown to New York from Turkey. He spoke through an interpreter, recounting how his wife had been trapped beneath the bus and died that night in the hospital.

“She was my everything,” he said, “and she was my best friend and she was my best companion.” He added: “It’s difficult. It’s — you know, to come as two individuals and to go back basically with a coffin.”

The next to testify were the Algerian honeymooners, Ms. Kerchouche and Mr. Fellahi. After the crash, Ms. Kerchouche had numerous surgeries as doctors struggled to repair her right arm, which had suffered extensive nerve and vascular damage, and her other injuries. She ultimately faced several hundred thousand dollars in medical bills. Unable to travel, she and Mr. Fellahi had to stay in the United States for more than four months as she recovered. Ms. Kerchouche, who worked for a bank, could not return to work.

Not long after the crash, Ms. Kerchouche got pregnant and gave birth to a healthy baby boy. But she could not hold her child, she testified, because one of her arms was permanently locked at a 90-degree angle. Nor could she write, drive a car or turn a door handle, she said. In time, she was diagnosed with post-traumatic-stress disorder.

“She’s like living, but dead in the same time,” her husband told the judge.

Ms. Seker, the Turkish college student, was unable to come to court, but she sent a letter to her lawyer, Jordan K. Merson, who read it to the judge. In the letter, Ms. Seker said the crash’s impact on her life had been endless. She was in constant pain — the crash broke both of her shoulders and some of her ribs, and she was left with a collapsed lung and other fractures. She had nightmares and was now afraid to sleep.

“Sometimes,” she wrote, “I wake up and feel like I am being thrown, like I was on the bus.”

In a recent interview, Ms. Seker said that before the crash, she had been training to be a competitive swimmer and also loved playing volleyball. Now she cannot engage in either sport.

“They said probably I will never be able to do them again,” she said. Like Ms. Kerchouche, she had also stayed in the United States for more than a month to recover, in her case forcing her to miss a semester of school.

In the courtroom, Judge Brown appeared perplexed by the challenge of comparing these cases.

“How do I do this?” he asked Ms. Seker’s lawyer, Mr. Merson. The judge cited Ms. Kerchouche’s case, mentioning her damaged arm. “She can’t hold her baby,” he said. “She can’t feel anything.”

“If your client’s injury is worth a seven-figure number, what’s her injury worth?” Judge Brown asked. “Do I owe her a 10-figure number?”

In June, the judge issued a 20-page opinion, detailing how he had apportioned the insurance fund. He said he had examined the victims’ medical bills, anticipated surgeries, home-care help, lost wages, funeral expenses and what he called “intangible losses,” including those for pain, suffering and emotional harm.

He ultimately found that more than 40 victims had sustained a total of $9.26 million in damages. But because of the limited insurance, he said, he could award only 54 percent of the amounts they were due.

“This $5 million, while a substantial sum, proves insufficient to fully compensate the victims for their losses,” Judge Brown wrote.

Ms. Kerchouche had sustained $1.36 million in damages, including $1.2 million for pain and suffering, the judge said. She would receive only $733,000.

The judge valued the case of Jyotsna Poojari, a 43-year-old passenger from Mumbai, India, who had suffered numerous serious injuries and died after 11 days, at $2.14 million, including $1.8 million for pain and suffering. Her estate would receive $1.15 million after the adjustment. It was the largest award.

The damages sustained by Ms. Bahsi, who was conscious while pinned beneath the bus and at the hospital before she died, were set at $1 million for pain and suffering, plus a small amount for funeral expenses. That total would be reduced to $542,000.

A 54-year-old woman who died from numerous blunt-force injuries to the head, chest and back was awarded $387,000 — reduced to $208,000 — for lost income, funeral and other expenses. But her estate was awarded no damages for pain and suffering after the judge said evidence suggested that she had been killed instantly.

Ms. Seker, the former college swimmer, was awarded $350,000 for emotional damages and anticipated surgical costs, but her award would be decreased to $188,000, the judge wrote.

Her lawyer, Mr. Merson, said that the bus was severely underinsured. “Five million dollars, when people are seriously injured, is just not enough,” he said.

The driver’s deposition helped show that E-World was also liable in the crash, another lawyer, Matthew H. Bligh, said.

In August, two months after the judge’s opinion, E-World’s insurance company filed papers saying it would deposit $3 million of insurance with the court to give to the victims. Even that additional sum will not cover the total compensation Judge Brown found to be warranted.

“There is very little justice in all of this,” said Kenneth R. Feinberg, the lawyer who administered the victim compensation fund established by Congress after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. “I try to avoid using that word because it connotes the idea that a moral fairness has been achieved. I don’t buy that.”

“I think these programs are really based on mercy,” Mr. Feinberg added, “not justice.”

But it has become clear to the victims that no amount of money could compensate their losses.

“That day, in that bus, in that accident, everyone lost something,” Mr. Bahsi told the judge. “I lost everything.”

Original story found here.